The first version of the programming language Python was created by

Guido von Rossum in 1990 and named after Guido's favorite comedy troupe

Monty Python's Flying Circus. Only later the publisher O'Reilly

associated the language with a snake and put one on the front page of

the first Python book "Programming in Python" that is currently

available in its third

edition.

Python is an interpreted, interactive, dynamic object-oriented

programming language. Unlike Java, it is possible to write Python

programs that are not object based, but all the libraries and modules

you will use are object based and many of the language features make it

easier to write code this way. Python has been used in many real-world

applications such as client- and server-side web applications, GUI and

database programming, parallel processing and networked applications. At

Google, for example, Python is used as one of the three primary

programming languages alongside Java and C++. Python is an

interpreted

language because code is automatically compiled to bytecode which is

then executed by a bytecode interpreter. Unlike Java or C++, there is no

need to compile a program before running it, compilation is handled in

the background by the Python interpreter. Like many other scripting

languages (Tcl, Perl, Ruby) Python excels at handling textual data; the

rich set of libraries that come bundled with the language (Batteries

Included) include many that deal with the web making it an excellent

language to develop server side web applications. Python is also a very

popular "glue language" that can be used to connect in a direct way to

existing libraries written in other languages.

To run Python programs you will need to ensure that you have a version

installed on your computer.

Note that on OS X there is a default installation of Python 2.x, to get

Python 3 you need to download and install the package from the Python

Website. Windows users will not normally have an

installed version of Python so need to download and install it.

Once you have Python installed, you can run the interpreter to enter and

run Python commands directly or run Python scripts. We'll start by

running the interpreter but most of the time you will be writing program

scripts (in .py files) and running them

On the Mac and on Linux, you can run the Python interpreter in a

terminal window by typing the python3 command (or possibly just

python if you don't have an older version installed as well). Here's

an example from my Mac (running OSX Lion):

To run a Python program (or script), first save your program code in a

file with a .py extension, then run it from the command line with the

python command:

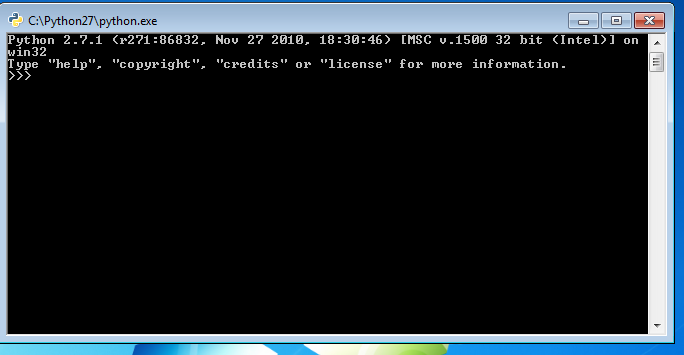

On Windows you can start an interactive Python session from the Programs

menu, find the Python entry under All Programs, within that you should

see Python (command line) which should start a command window running

the Python interpreter.

The Python console on Windows

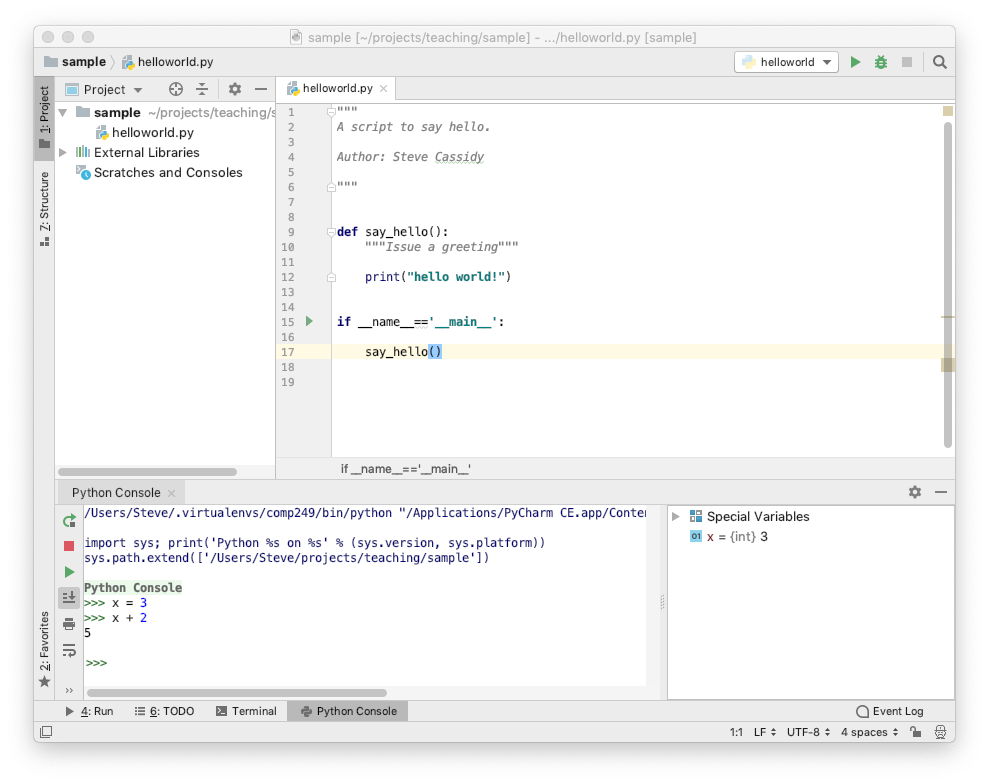

### Python in PyCharm

[PyCharm](https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/) is an Integrated Development

Environment (IDE) for Python that provides a number of features to make

writing and debugging Python code easier. It also supports web

development well with support for HTML and CSS files. There is a

free version of PyCharm labelled PycharmCE (Community Edition) which is

great for general development work. You can also get [student versions](https://www.jetbrains.com/student/) of

the software to use while you are studying.

PyCharm allows you to open any working directory as a project and allows

you to run Python code from within the IDE. You can do this via a

Python Console as shown in the screenshot below or via the green

'Run' icon. Output from running your code is shown within the IDE.

PyCharm also supports the Python debugger and a test runner that

will show you the results of running your Python unit tests in

an interactive way. Finally, PyCharm integrates Version Control

and provides a nice interface to committing changes and interacting

with remote repositories.

Of course, PyCharm is not the only IDE that supports Python, you may

already use another IDE or editor for programming and it may support

Python or have extensions that do so. We will sometimes refer to

PyCharm in this text but nothing here assumes that you are using

it over any other way of editing and running your code.

### Summary

Once you have started the Python interpreter, the language is the same

on every platform. We recommend running your code from within Eclipse

but you may want to find your own way of working with Python using your

own favourite tools.

In the remainder of this text we will use many examples. Some of these

will be examples of interaction with the Python interpreter, in these

you will see the interactive prompt `>>>` displayed at the start of the

line. We will use this where we want to highlight the result of an

interactive computation. Other examples show Python code that you can

cut and paste into your programs or directly to the interpreter. Here's

an example that shows an interactive command and its output highlighted

in a different colour:

>>> print("Hello World")

Hello World

and here's one that is intended to be saved in a file:

Variables

---------

Let us start with variables. A variable is something whose value can

change over time. A variable comes into existence the first time you

assign it a value. You do this with an assignment statement (=) which

binds the variable name to an object. In Python, an object can be a

number, a string, a list, and so on, for example:

>>> x = 5 # number

>>> x

5

>>> x = 'Britney' # string

>>> x

'Britney'

>>> x = [5,'Britney'] # list

>>> x

[5, 'Britney']

In this example, the same variable name is given different types of

value. The `#` symbol introduces a comment, the remainder of the line is

ignored.

The names of Python variables must follow the following conventions:

- names start with a letter or underscore followed by any number of

letters, digits, order underscores;

- names are unlimited in length;

- names cannot be keywords.

Python variables are not restricted to any particular datatype and any

variable can represent any object. Python takes care of type issues

behind the scenes: like other dynamic languages, all type-checking is

performed at run-time by the interpreter. Therefore, Python is called a

*dynamically typed programming language* because you never have to

declare anything in advance as you do, for example, in a statically

typed language like Java.

Dynamic typing is a double edged sword. On one hand it allows you to be

flexible in the way you write your code. On the other hand it means you

don't need to declare things that might prevent bugs when your code is

run. If you assume that a parameter to a procedure contains an integer

and someone sends you a string, your code will crash (or behave

strangely).

Note: Technically variables hold references that point to objects stored

in memory.

Numbers

-------

You can use the Python interpreter directly as a simple calculator

together with the standard operators ( +, -, \*, or / ) and standard

calculation order:

>>> 2 + 3

5

>>> 2 + 3 * 4

14

>>> (2 + 3) * 4

20

Of course, you can assign numbers to variables and then do the

calculation:

>>> first_number, second_number, third_number = (2, 3, 4)

>>> result = first_number + second_number

>>> result

5

>>> result = first_number + second_number * third_number

14

>>> result = (first_number + second_number) * third_number

20

You can compare numbers using the following comparison operators (<,

<=, >, >=, ==, or !=):

>>> 20 > 14

True

>>> 14 > 20

False

>>> first_number < second_number != third_number

True

If an expression contains mixed types, then Python converts numbers

internally to common type for evaluation, for example:

However, you can convert a number explicitly to a specific type - if

necessary:

Assignment expressions such as

>>> x = 1

>>> x = x + 2

>>> x

3

are so common in programming languages that Python provides augmented

assignment operators as shortcus, try:

>>> x = 0

>>> x += 1

>>> x -= 2

>>> x *= 3

>>> x /= 2

>>> x ** 2

4

>>> x %= 7

>>> x

5

Strings

-------

A string is a sequence of zero or more characters surrounded by singe

quotes ('), double quotes (") or three single or double quotes (''' or

"""), called a triple-quoted string, for example:

>>> str1 = 'Alecia'

>>> str1

'Alecia'

>>> str2 = "Alecia Beth Moore"

>>> str2

'Alecia Beth Moore'

>>> str3 = """Alecia Beth Moore

professionally known as Pink"""

>>> str3

'Alecia Beth Moore\nprofessionally known as Pink'

Note that single- and double-quoted strings must be specified on one

line. Triple-quoted strings may span multiple lines. You can embed

single quotes in a double-quoted string and vice versa, and single and

double quotes in a triple-quoted string. Note also that triple-quoted

strings retain their formatting.

Python concatenates the two lines to a single string with a newline

(\\n) character. So, if you print the string, then the output looks as

follows:

>>> print(str3)

Alecia Beth Moore

professionally known as Pink

Strings are sequences and like all sequence types in Python we can find

their length with the `len` function:

>>> len(str1)

6

>>> len(str2)

17

Strings are ordered sequences of characters and an individual character

can be identified by its position (= index), for example:

>>> str1

'Alecia'

>>> str1[0]

'A'

>>> str1[1]

'l'

>>> 'Alecia'[3]

'c'

Sometimes you want to extract (= slice) a substring from a string. A

slice is a substring of a string specified by two indexes, for example:

>>> str1[2:4]

'ec'

>>> str1[1:-1]

'leci'

>>> str1[2:]

'ecia'

>>> str1[:2]

'Al'

Two strings can be concatenated (glued together) with the (+) operator,

and repeated with the (\*) operator, for example:

>>> str4 = 'I Am'

>>> str5 = ' A Rock Star'

>>> str6 = str4 + str5

>>> str6

'I Am A Rock Star'

>>> str7 = str4 + str5*3

>>> str7

'I Am A Rock Star A Rock Star A Rock Star'

Python provides many built-in string methods for manipulating strings;

here are a few of them:

>>> str1.upper()

'ALECIA'

>>> str1.lower()

'alecia'

>>> str1.find('ci')

3

>>> str1.upper().find('A')

0

>>> str1.replace('cia','x')

'Alex'

Sometimes you need to get rid of white space before and/or after a

string. Trimming strips white space from the beginning and the end of a

string and is often used to clean up the user input:

>>> str7 = ' get rid off white space '

>>> str7.lstrip()

'get rid off white space '

>>> str7.rstrip()

' get rid off white space'

>>> str7.strip()

'get rid off white space'

Splitting a string divides the string into substrings and puts them into

a list. Joining is the inverse of splitting. One or more delimiter

characters separate the individual substrings during split and join

opertions, and a "maxsplit" parameter can be used to specify how many

times a string should be splitted:

>>> str8 = 'John Miller, 22 Essex Street, 2121 Epping, Sydney'

>>> str8.split(',')

['John Miller', ' 22 Essex Street', ' 2121 Epping', ' Sydney']

>>> str8.split(', ')

['John Miller', '22 Essex Street', '2121 Epping', 'Sydney']

>>> str8.split(', ',1)

['John Miller', '22 Essex Street, 2121 Epping, Sydney']

>>> words = str8.split(',')

>>> ' '.join(words)

'John Miller 22 Essex Street 2121 Epping Australia'

>>> ','.join(words)

'John Miller, 22 Essex Street, 2121 Epping, Australia'

Note that delimiter characters do no occur as part of substrings in the

resulting list and white space characters count as single delimiters. If

the "maxsplit" parameter is omitted, all possible splits are made.

Note also that in Python strings are *immutable* sequences of

characters; you can't actually modify a string, you need to make a new

string with any changes you want.

Sometimes it is useful to treat a string as a list of characters. You

can convert a string into a list and perform list operations on this

list, and then convert the resulting list back into a string, for

example:

>>> chars = list('fedcba')

>>> chars

['f', 'e', 'd', 'c', 'b', 'a']

>>> chars.sort()

>>> chars

['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f']

>>> newstring = ''.join(chars)

>>> newstring

'abcdef'

Lists

-----

As already discussed, lists are ordered sequences of objects and can

contain any type of other objects. Lists are like arrays in other

programming languages and can grow and shrink as needed. In order to

create a list, simply enclose zero or more items in brackets:

>>> lst1 = ['apple','peach',['pumpkin','melon'],[1,2,3]]

>>> print(lst1)

['apple', 'peach', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], [1, 2, 3]]

Like strings, lists are a sequence type and we can find the length

of a list with the `len` function:

An individual item in a list is identified by its position similar to a

character in a string, for example:

>>> lst1[2]

['pumpkin', 'melon']

>>> lst1[-1]

[1, 2, 3]

Nested items can be accessed with multiple indexes, for example:

>>> lst1[2][1]

'melon'

>>> lst1[3][0]

1

You can extract a slice of a list by specifying the two indexes that

demarcate a sequence of items, for example:

>>> lst2 = [1,2,3,4,5,6]

>>> print(lst2[0:2], lst2[1:3], lst2[-3:-1])

[1, 2] [2, 3] [4, 5]

You can use the (+) operator to concatenate two lists:

>>> lst3 = lst1 + lst2

>>> lst3

['apple', 'peach', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], [1, 2, 3], 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

There is an operator (in) that can be used to test if a particular item

is part of a list or not:

>>> 'apple' in lst1

True

>>> 'apple' in lst2

False

>>> 4 not in lst1

True

>>> 4 not in lst2

False

In Python, there exist a number of built-in methods and operations that

can be used to modify a list. Here is a small selection of them:

>>> lst1.append('tomato')

>>> lst1

['apple', 'peach', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], [1, 2, 3], 'tomato']

>>> lst1.insert(1,'lemon')

>>> lst1

['apple', 'lemon', 'peach', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], [1, 2, 3], 'tomato']

>>> lst1.remove([1,2,3])

>>> lst1

['apple', 'lemon', 'peach', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], 'tomato']

>>> lst1.index('lemon')

1

>>> lst1[1] = 'lime'

>>> lst1

['apple', 'lime', 'peach', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], 'tomato']

>>> lst1[0] = []

>>> lst1

[[], 'lime', 'peach', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], 'tomato']

>>> lst1.sort()

>>> lst1

[[], ['pumpkin', 'melon'], 'lime', 'peach', 'tomato']

>>> lst1.reverse()

>>> lst1

['tomato', 'peach', 'lime', ['pumpkin', 'melon'], []]

Tuples

------

Tuples are ordered sequences of objects that are enclosed in

parentheses. At the first glance, tuples look very similar to lists but

the difference is that tuples cannot be modified. That means tuples are

immutable like strings and have a fixed length. Many tuple and list

operations are the same, apart from those operations that you can use to

modify a list. So why do we need tuples at all? Tuples are faster to

access and consume less memory than lists, and they are handy if you

want to make sure that your data cannot be modified. Here is an example

that illustrates what you can do with tuples and what not:

>>> tup1 = ('apple', 'peach', ('pumpkin','melon'),(1,2,3))

>>> tup1[2][1]

'melon'

>>> tup1.append(4)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<pyshell#74>", line 1, in <module>

tup1.append(4)

AttributeError: 'tuple' object has no attribute 'append'

As you can see above, if you attempt to use the "append()" method that

works for lists on a tuple, Python will rise an AttributeError exception

since tuples have no methods - you cannot append anything to a tuple.

Remember: tuples are immutable.

Tuples are another sequence type and we can find their length with the `len`

function:

An annoying feature of Python syntax is that parentheses do double duty

as the delimiters of a tuple and for identifying parts of expressions.

So, I can write an expression:

and x would get the value 5 as you would expect. But what if I wanted to

assign x to a tuple containing the number 5?

Python can't tell that this is supposed to be a tuple rather than an

expression, so it defaults to treating it as an expression and assigning

5 to x. To get a tuple, you need to insert a comma after the value:

There are a number of situations where you will need a tuple of one

thing and this will most likely bite you - the error messages will look

wierd and you won't be able to see what the problem is. You've been

warned!

Dictionaries

------------

Dictionaries are another data structure that hold a collection of

arbitrary objects (values). In contrast to a list where each value is

accessed by an index, a dictionary uses an unique identifier (= key) to

access a value. Dictionaries (also known as associative arrays) consist

of zero or more comma-separated key-value pairs that are enclosed in

braces. The key and its value are separated by a colon (:):

>>> dict1 = {'first_name':'John', 'second_name':'Miller', 'profession':'plumber', 'age':'32'}

>>> print(dict1)

{'age': '32', 'first_name': 'John', 'profession': 'plumber', 'second_name': 'Miller'}

As the example above illustrates, dictionaries are unordered. This is

because Python stores key-value pairs in a way that speeds up the key

lookup and you cannot control how this is done internally. That means

you have to consider dictionaries as randomly ordered.

Python provides a number of operators and methods to retrieve values and

key-value pairs from a dictionary:

>>> dict1['age']

'32'

>>> dict1.values()

dict_values(['plumber', 'Miller', 'John', '32'])

>>> dict1.keys()

dict_keys(['profession', 'second_name', 'first_name', 'age'])

>>> dict1.items()

dict_items([('profession', 'plumber'), ('second_name', 'Miller'), ('first_name', 'John'), ('age', '32')])

>>> 'profession' in dict1

True

>>> len(dict1)

4

Note that `dict_values`, `dict_keys`, `dict_items` are [dictionary view

objects](https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#dictionary-view-objects).

Quite often, you'll be converting the output to a list, like so:

>>> keys = list(dict1.keys())

>>> print(keys)

['profession', 'second_name', 'first_name', 'age']

>>> values = list(dict1.values())

>>> print(values)

['plumber', 'Miller', 'John', '32']

>>> items = list(dict1.items())

[('profession', 'plumber'), ('second_name', 'Miller'), ('first_name', 'John'), ('age', '32')]

Like lists, dictionaries are mutable, you can add and remove key-value

pairs and combine dictionaries, for example:

>>> dict1['salary'] = '75000'

>>> dict1

{'salary': '75000', 'age': '32', 'first_name': 'John', 'profession': 'plumber', 'second_name': 'Miller'}

>>> del dict1['profession']

>>> dict1

{'salary': '75000', 'age': '32', 'first_name': 'John', 'second_name': 'Miller'}

>>> dict1.clear()

>>> dict1

{}

>>> dict2 = {'one':'un', 'two':'deux', 'three':'trois'}

>>> dict3 = {'four':'quatre', 'five':'cinq'}

>>> dict2.update(dict3)

>>> dict2

{'four': 'quatre', 'three': 'trois', 'five': 'cinq', 'two': 'deux', 'one': 'un'}

Control Flow Statements

-----------------------

Control flow statements determine the execution sequence of statements

in a program. The most important control flow statements are: `if`,

`for`, `while`, and `try`.

Indentation is Python's way of grouping statements! There are no braces

like in Java or C++, just indentation, this can be a source of confusion

because you need to be consistent in how much indentation you use in a

block, common problems come from mixing spaces and tab characters for

indentation, so be sure to configure your editor to use spaces for

indentation if you are able to do so. The Python style guide suggests

that you indent by four spaces for each block. You can probably

configure your editor (eg. Eclipse) to use spaces instead of tabs when

it indents Python code. Whatever you do, be consistent.

Control flow statements consist of a header line followed by one or more

indented statements. The header line always ends with a colon (:) and a

block of indented statements. Python requires that a block contains at

least one statement (you can use the `pass` statement to create a null

statement if the logic requires one).

When you enter statement blocks in the interactive Python interepreter

the prompt changes from `>>>` to `...` when you are inside the block, to

finish the block you need to enter a blank line with no indentation.

The `if` statement is a conditional statement and executes a block of

statements, if a Boolean expression is true - for example:

>>> numbers = [3,2,5,1,4]

>>> numbers.sort()

>>> num1 = 2

>>> num2 = 4

>>> if (num1 < num2) and (num1 in numbers) and (num2 in numbers):

... print(num1, 'precedes', num2, 'in a sorted list')

...

2 precedes 4 in a sorted list

The `for` statement is an iterative statement that loops over a sequence

of values. Unlike in C++ or Java, the for loop doesn't use a counter and

end condition; instead it binds a variable to subsequent values within a

sequence. This is useful since the most common use for a for loop is to

operate on all members of a sequence in order - for example:

>>> numbers = [3,4,1,9,5]

>>> for number in numbers:

... print(number)

...

3

4

1

9

5

If you do want a counted loop analogous to a Java or C++ for loop then

you need to generate a sequence of numbers, the `range` function can be

used for this. `range(10)` generates a seqence of 10 numbers from 0 to

9. Here's an example:

>>> for index in range(5):

... print(index, ":", index*index)

...

0 : 0

1 : 1

2 : 4

3 : 9

4 : 16

If you are coming from a background in another programming language, it

is tempting to use counted for loops like the above more than is

necessary in Python. Most for loops are iterations over a sequence and

the counter variable is used to index into the sequence. In Python, the

for loop variable iterates over the sequence for you so you almost never

need to use an index variable. Always think `for number in numbers:`

rather than `for index in range(len(numbers)):`.

The `while` statement is an interative statement that repeats a block of

statements as long as a condition remains true - for example:

>>> n = 5

>>> i = 1

>>> while i <= n :

... print(i, 'x 3 =', i*3)

... i = i + 1

...

1 x 3 = 3

2 x 3 = 6

3 x 3 = 9

4 x 3 = 12

5 x 3 = 15

Examples

--------

A good example of how dictionaries are useful is shown in this example

which uses a for loop to count the frequency of words in a list. The

dictionary is used to store the fequency of a word, when a new word is

found, the count is set to 1, if the word exists, the count is

incremented.

words = ["one", "two", "one", "two", "three", "four", "one"]

freq = dict()

for word in words:

if word in freq:

freq[word] += 1

else:

freq[word] = 1

for word in freq.keys():

print(word, ":", freq[word])

Do the same thing for the subsequent program: it illustrates the use of

an "if-elif-else" conditional. Here the "elif" clause tests for

additional independent conditions after the "if" statement, and the

"else" clause specifies the statement that is executed, if none of the

precededing conditions is true:

string = input('Enter your age: ')

age = int(string)

if age < 0:

print('You entered a negative number.\n')

elif age < 3 or age > 100:

print('You are too young or too old to use this program.\n')

else:

print('This corresponds to', age*7, 'dog years.\n')

Note that the built-in function `input()` prompts the user for input.

What happens if you don't input a number into the program but a string

instead? How can you fix this problem?

The subsequent example uses a "for" loop and an "if-else" conditional -

what does the program compute?

names = ['Rob', 'Bill', 'Sue', 'Marc', 'Sue']

names.sort()

duplicate_counter = 0

previous_name = names[0]

del names[0]

for name in names:

if previous_name == name:

duplicate_counter = duplicate_counter + 1

print('Duplicate found:', name)

previous_name = name

if duplicate_counter == 0:

print('No duplicates were found')

else:

print('Number of duplicates found:', duplicate_counter)

Copyright © 2009-2012 Rolf Schwitter, Steve Cassidy, Macquarie

University

[](http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/)\

Python Web Programming by

Steve

Cassidy is licensed under a [Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License](http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).