`apt-get` is also used to keep your system up to date and install new

versions of packages if they have been released. You can run one command

to update the list of packages the system knows about:

This should display a long list of status messages as it checks against

various online repositories for the latest versions of software. It is

sometimes necessary to do this before you can install any new software,

so if installing nginx fails, try doing this and then re-running the

nginx install.

To update the system to the latest versions of all installed programs

enter:

This will find which programs need updating, show you a list and ask if

you want to proceed. If you say yes, it will download the new versions

and install them in place of the old ones. If you are running a server

that is exposed to the Internet then it is very important that you do

this regularly to avoid security issues.

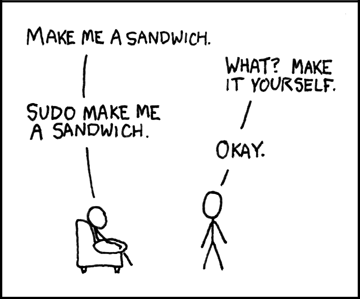

The result is an error message saying I don't have permission to do

this. The reason is that on a Linux system, a regular user doesn't have

permission to read and write system files. There is a special user

called 'root' (or the superuser) who is allowed to do this. This

protects the system from accidental or malicious damage. To actually

install software I need to login as the root user rather than `webdev`.

I could log out and log in again as root, but since it is quite common

to want to run commands as the root user, there is a short cut via the

`sudo` (superuser do) command:

The result here is that we are prompted for a password, if that matches

ok then the command is run as root and the package is installed. You

will be asked if you want to install various other applications that

nginx requires to run, you can just hit return to accept the default

response which is Y (yes).

If all goes well, you will now have nginx installed on your virtual

machine. The installation process also makes sure that the server is

running (and that it will re-start whenever you re-start your VM). By

default, it will listen for requests on the default port 80 and serve up

a single static page that has been installed along with the software.

However, since we don't have a web browser on the VM, we can't test

it...or can we?

In fact we can test it with a few different tools that are installed by

default in our VM. The easiest is probably `curl` which is a command

line tool to retrieve URLs. Since the server is running on the local

machine using port 80, the URL for the main page will be

`http://localhost/`. So, to get the page we enter:

The `sudo` command is an all powerful tool - take care when using it!

[ Source:

XKCD](https://xkcd.com/149/)

So in my case it is working; nginx has served up the test page included

in the distribution. If you're trying this and it did not work then a

number of things could be the cause of the problem. Firstly, did you see

any error messages when you installed nginx - if so read these carefully

and try to work out what the issue is. Note the comment above about

running `apt-get update` to enable the system to find newer pacakges. If

all seemed to go well but it just doesn't work, you can check to see

that the server is running with the following command:

$ sudo service nginx status

This may report that nginx is running or not. You could try restarting

it with the command:

$ sudo service nginx restart

If this doesn't fix the problem then the best option is to search the

web for possible solutions - this is reasonably effective if you have an

error message generated at some point in the process. Search for the

text of the error message - you are probably not alone in having this

problem.

Shared Folders

--------------

A useful feature of VirtualBox is the ability to share folders between

the host operating system (your laptop) and the VM. This means that you

can have the code of your Python application in a folder on your laptop

but then have the same directory available inside your VM. This saves

having to copy your code into the VM every time you want to test it. You

can edit in your favourite editor on your laptop and run the code from

inside the VM.

To achieve this we need to install what are called "Guest Additions" to

the target operating system. These are some extensions to the Linux

kernel that allow it to coordinate with the VirtualBox subsystem. They

also help with integrating the mouse and cursor and copying/pasting

between the host system and the VM. To do this take the following steps:

$ sudo apt-get install virtualbox-guest-utils

The next step is to set up a shared folder via the VirtualBox

application. From the menu select *Devices* and *Shared Folders* then

*Shared Folder Settings...*. In the settings pane create a new shared

folder via the + icon on the right. Enter `share` as the folder name

and select the directory containing your application source code for the

folder path. Make sure *Auto Mount* is checked and click Ok.

Another small change is to add our username on the VM to the special

group `vboxsf` so that we can get access to the shared folder contents.

$ sudo adduser webdev vboxsf

To have this all take effect, we need to reboot the virtual machine:

Now, when you login to your machine you should be able to see the

contents of the folder on your host machine under `/media/sf_share`, eg.

using the `ls` command:

We can now move on to configuring the network on the VM in preparation

for getting our web application running.

Network Connection

------------------

The virtual machine is running inside a simulated environment where

system resources are presented to it through an emulation layer. By

default the VM you created will use Network Address Translation (NAT) to

connect its network to that of the host machine. This is the same

mechanism that your home router uses to allow you to share one IP

address between all of the machines on your home network. This works

well to allow the VM to connect to the outside network since traffic is

routed through the host machine's network connection automatically.

The main reason for setting up this VM is to allow us to run a web

server on the machine to test our web application in a realistic server

environemnt. To make this work we need to be able to access the network

ports on the VM from the host machine. By default, the VM doesn't have

an IP address that is visible from the host. The easiest way to get

network access to the machine is to set up a *port forwarding* rule on

the VM. This will connect a port on the VM with a port on the host.

To achieve this, while your VM is not running, look at the settings of

your VM in VirtualBox. Select the Networking tab and click on the

Advanced button, you should then see a Port Forwarding button. Clicking

this shows an interface that allows you to enter a new mapping. Here you

will enter a new rule to connect port 80 on the VM to a free port on the

host machine, eg:

Name Protocol Host IP Host Port Guest IP Guest Port

------ ---------- ----------- ----------- ---------- ------------

HTTP TCP 127.0.0.1 8500 80

This rule will forward traffic form port 80 on the VM to port 8500 on

the host machine's 127.0.0.1 IP address (8500 is just an unused port

number). This means that the nginx web server that we configured to

listen to port 80 will be accessible via the url

`http://127.0.0.1:8500/` on the host machine.

The same method could be used to set up rules for other ports. If you

want to be able to use ssh to connect to the VM as you would a remote

machine you can connect the ssh port (22) to a free port (eg. 2222) on

the host and then use an ssh client (e.g. Putty on Windows or the ssh

command on Mac) to connect to 127.0.0.1:2222. Accessing your VM using

ssh is a good idea because it will familiarise you with the way that you

would access a remote server. The interface is the same command line

prompt but you will be typing commands into a terminal window (or a

Putty window) on your host machine rather than into the VirtualBox

emulator window.

Serving a Python Application

----------------------------

The overall goal of this chapter is to show how to configure a Linux

server to run a Python web application in a way that mirrors a

real-world deployment. So far we have a running nginx web server and

we're able to connect to it from the host machine. The server is

configured to serve static pages; the next task is to get the Python web

application to run inside the VM, we will then connect it to the nginx

server to complete the task.

### Install Bottle

Python version 3 is installed by default in the Ubuntu system but we

need to install the Bottle module with the command:

$ sudo apt-get install python3-bottle

(note that you could also install bottle using the Python package

manager `pip`, on Ubuntu, using `apt-get` is a good idea because it can

also be used to upgrade packages easily as security patches are

released).

### A Sample Application

As a sample application for deployment I will use a version of the AJAX

list maker project from [chapter on AJAX](../javascript/ajax.md). This makes

use of a simple SQLite database and has a few resources that are served

as static files (Javascript, stylesheet and an image). You can download

these here:

- [jsonlikes.py](code/jsonlikes.py)

- [database.py](code/database.py)

- [views/jsonlikes.tpl](code/views/jsonlikes.tpl)

- [static/likes.js](code/static/likes.js)

- [static/style.css](code/static/style.css)

- [static/logo.png](code/static/logo.png)

or as a single zip file [jsonlikes.zip](code/jsonlikes.zip).

If you are following along with this exercise you could download these

files and copy them to a the shared folder that you set up earlier on

your machine or choose a project of your own to deploy. Be sure to get

the directory structure right for these files with the views and static

files in a subdirectory relative to the two Python files. Test the

application by running it as usual through PyCharm (or however you

usually run your Python applications).

### Running the Application

Inside the VM we can now run the Python application. The easiest way to

do this is to change our working directory to the shared folder

(`/mnt/sf_share`) and run the application from the command line using

the Python interpreter. This can be done as follows:

$ cd /media/sf_share

$ python3 jsonlikes.py

You should see the familiar output of the Bottle development server

indicating that it is listening on port 8080 for HTTP traffic:

$ python3 jsonlikes.py

Bottle v0.12.8 server starting up (using WSGIRefServer(restart=True))...

Listening on http://127.0.0.1:8080/

Hit Ctrl-C to quit.

If you get this message then it looks like the application is working

but again we face the problem that we can't test it. Even worse than

with nginx, we can't even use `curl` to test it because it's taken over

the command line - we can't run commands while it is running the server.

To get around this we will run the server as a *background process*

which means that it will run but will not take over the command line. To

do this we do two things on the command line. The first is to redirect

the output that the server produces to a file; this is done by

redirecting the output to the file `web.log` using the `&>` directive.

The second is to indicate that we would like to run the process in the

background by adding `&` to the end of the command line.

$ python3 jsonlikes.py &> web.log &

[1] 1204

The output produced by the command is in two parts, the first number in

square brackets indicates that this is the first background process I

have running in this shell. The second is the system process id number.

Take note of these as we'll use them later to kill the server process.

We can now use `curl` once again to test that the server is working.

This time the server is listening on port 8080 so the command is:

$ curl http://localhost:8080/

You should see some HTML output if all is working well. If you are

running the `jsonlikes.py` application linked above, you could also try

the /likes URL which returns a JSON list of the current set of likes:

$ curl http://localhost:8080/likes

Once we have verified that this works we can halt the server by stopping

the python process. To do this we need the numbers that were printed out

when we ran the server earlier. The easiest option is to use the first

number, which is usually 1 if you are just running one server process.

We use the kill command to send a SIGINT interrupt signal to the

process:

The alternative is to use the process number:

The Bottle server we are running here is not meant for a real

deployment, it is only intended as a development server for very

lightweight use. It can only cope with one request at a time and so

would fail under any kind of load from the web. In a real production

situation you would use a real application server such as

[gunicorn](http://gunicorn.org/) or

[uWSGI](https://uwsgi-docs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/). Both of these are

Python specific application servers that can run your Bottle application

in a way that is more robust and able to handle real traffic. For

example, they will run more than one worker thread to handle multiple

requests at once. You should experiment with these servers to learn more

about a complete Python application deployment environment.

Both should have the effect of stopping the process and printing a

message to that effect. Now that the process is stopped we can examine

the log file `web.log` that should contain the output of the server when

we made the requests. Use the `cat` command to show the file contents:

$ cat web.log

Bottle v0.12.7 server starting up (using WSGIRefServer(restart=True))...

Listening on http://127.0.0.1:8080/

Hit Ctrl-C to quit.

127.0.0.1 - - [25/May/2016 02:00:32] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 692

127.0.0.1 - - [25/May/2016 02:00:35] "GET /likes HTTP/1.1" 200 36

/usr/lib/python3/dist-packages/bottle.py:3116: ResourceWar...

(The last line is just an error message generated when we stopped the

server.)

At the end of this section, we now have a running web application on the

VM that is listening to port 8080 and serving pages. However this isn't

connected to the outside world since we only connected the real HTTP

port (80) to our local network. We have the `nginx` server running and

listening to port 80 but only serving static files. The next part of the

puzzle is to connect these two together.

Note that `nginx` can't directly run Python programs so we can't run our

application directly. `nginx` will act as a *proxy server*, accepting

requests on port 80 from the outside world and forwarding them to our

running Python server on port 8080.

nginx Configuration

-------------------

nginx is a web server but is particularly focussed on providing a

front-end server that can efficiently accept requests and forward them

to one or more back-end services. This is known as a *reverse proxy* and

is one of the ways of making web services more robust and able to handle

larger volumes of traffic. We will configure nginx here to pass requests

on to our Python web application listening on port 8080.

The nginx configuration is held in the directory `/etc/nginx/` (you will

find the configuration of most services on your Linux server in the

`/etc` directory). We will look at the configuration found in

`/etc/nginx/sites-available/default` which is the default configuration

that comes with the package. The default configuration contains a lot of

comments but the core configuration is as follows:

server {

listen 80 default_server;

listen [::]:80 default_server;

root /var/www/html;

# Add index.php to the list if you are using PHP

index index.html index.htm index.nginx-debian.html;

server_name _;

location / {

# First attempt to serve request as file, then

# as directory, then fall back to displaying a 404.

try_files $uri $uri/ =404;

}

}

In this configuration, the server is told to listen to the default port

80 and serve static files from the directory `/var/www/html`. The

location part defines the handling of all URLs starting with `/`, in

this case serving static files or directory listings.

Instead of this configuration we want to have all requests for URLs

starting with `/` forwarded to our Python web application listening on

port 8080. This is done with the `proxy_pass` directive as follows:

server {

listen 80 default_server;

listen [::]:80 default_server;

root /var/www/html;

server_name _;

location / {

proxy_pass http://localhost:8080;

}

}

To create this configuration you need to modify the

`/etc/nginx/sites-available/default` file. The easy way to do this is to

save the above text in a file in your shared directory and then inside

the VM, copy the file to the nginx directory:

$ sudo cp /media/sf_share/default /etc/nginx/sites-available/default

We need to use `sudo` here because ordinary users are not allowed to

modify these configuration files.

We also need to make sure that the file has the permissions to be read

by any user. To ensure this, we can use

`sudo chmod a+r /etc/nginx/sites-available/default`, which means "enable

read permission to all users". You can then check that the permissions

are correct by typing `ls -l /etc/nginx/sites-available/default` and

observe the result. There should be three `r` on the left-hand side of

the listing of the file:

total 4

-rwxr-xr-- 1 root root 163 May 27 10:28 default

The above example also says that the file can be written by the root

(the first `w`) and can be executed by the user root and the user group

associated with the root (the two `x`).

The alternative way to modify the configuration is to use an editor on

the VM itself. The standard text editor on a Linux server is `vi` and

most people will find it very confusing. However, if you are going to be

working with remote servers it is a good idea to have at least a basic

familiarity with `vi` to allow you to make quick changes to files. There

are a number of tutorials on the web that will help you learn about

`vi`, e.g. [from Gentoo](https://wiki.gentoo.org/wiki/Vim/Guide), [from

WikiBooks](https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Learning_the_vi_Editor), [from

IBM](http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/library/l-lpic1-v3-103-8/).

Once the new version of the configuration file is in place we need to

restart the server configuration to have it take effect. Do this with

the following command:

$ sudo service nginx restart

To test this setup we can again use `curl` from inside the VM to access

the pages served by `nginx`:

This should show the output generated by the Python application

(assuming it is still running in the background as established above).

If this doesn't work, check that the Python process is still running

(use `curl` again to access the server on port 8080). Look at any error

messages that you get when you get the pages with `curl`. You can also

see error messages in the `nginx` logs which are stored in

`/var/log/nginx/`. You can look at the contents of these files with the

`more` program, e.g.:

$ more /var/log/nginx/access.log

$ more /var/log/nginx/error.log

We are now ready to try to access our application from outside the VM.

If the network is configured for port forwarding as discussed above, the

`nginx` web server should be available at `http://localhost:8500` from

the host machine (your laptop). If this works then give a little cheer!

If not, check that your network port forwarding configuration is

correct.

### Serving Static Files with nginx

One final modification we can make to the configuration is to have

`nginx` take over the job of serving static files for our application.

Static files by definition do not change and there is no need to have

our Python script involved in serving them. `nginx` is good at serving

static content and can do it more efficiently that our Python server.

To enable this, we need to configure the URL `/static` to be served

directly through `nginx`, bypassing the Python server. Add the following

lines to the configuration after the existing location clause:

location /static {

root /media/sf_share;

}

Since the files we want the server to access are stored on the shared

folder, we need to give it permission to do so. By default these files

are only readable by members of the `vboxsf` group, so we need to add

the user `www-data` to this group (the nginx server runs as this user).

$ sudo adduser www-data vboxsf

Restart the server again and check that the application is still working

- in particular that the static resources (stylesheet, javascript and

image files) are being served.

Summary

-------

This chapter has walked through the configuration of a Virtual Machine

based Linux web server for running a simple Python web application. The

example has been made as simple as possible but is typical of a real

configuration that might be used to serve a small web application. Part

of the motivation for this chapter is to introduce web development

students to the Unix command line and the basics of working with Unix

applications. The interested student should take this as a starting

point and explore further to learn to master the Unix environment.

There are still a few things to do before the configuration described

above is a realistic one. I'll note some here for completeness although

I won't go into detail.

- Use a production database rather than SQLite. SQLite is fine for

development and even for small scale services but a real deployment

will make use of a database like Postgres or MySQL.

- As mentioned above, the Python web application should be served

using a server like gunicorn rather than the default Bottle

development server.

- Of course for a real deployment we won't run a VM on our own laptop

but all of the same concepts apply to Virtual Machines provided by

vendors such as Amazon (AWS), Microsoft (Azure) or Google

(Cloud Platform).

[](http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/)\

Python Web Programming by

Steve

Cassidy is licensed under a [Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License](http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).